Once

An Essay by Paola Anselmi

The photographic series Eight documents one of the most personal, self reflexive, often unspoken and possibly least understood of all human states; death. The impetus for the photographic undertaking dates back six years when Chris’ father became ill and ultimately died. Over the last two years he has almost exclusively focussed on this project. Eight is as much about words as it is images, both encapsulate some of the most private, intimate moments with those they love; beautiful, heart wrenching real events about real people.

Across the South Western regions of the state, many of which still retain a strong sense of their pioneering past and possibly a less corporatised approach to tradition, Chris became personally involved with those facing the inevitable approach of one’s own death, bereaved family members, professionals whose interventions balance treatment and its uncertainties and those who may assist you to the edge of life.

Eight is a collective of experiences and stories that chronicles open-ended visions of death, the evolution of suffering and the reclamation of life through memory. The project absents from romanticist overtones, lyrical and over-sentimentalised images, which might have interfered with the authenticity of the experience and reduced the often-difficult reality of mortality to cliché.

This reality is that we face death daily. It can happen to any of us at anytime.

The nature of death and our individual cognisance of end-of-life experience have been a central concern for humanity and underpin cultural, religious and conceptual explorations, both physical and metaphysical across the globe.

Flowers. There are lots of flowers but somehow even these seem listless somehow. Their softness of colour, a few stems crowded in a modest vase speak more about convention and habit rather than a determined effort to animate an area or brings brightness into a room. In some cases they create a sense of melancholy despite intending the opposite response.

Death is defiant. Even if we attempt to strip away all the belief systems that accompany how we acknowledge and respond to a death, given its inhered and opposing binary relationship to living, simply distinguishing death, as the antonym to life, remains complex. The moment when life ends, when the last breath is inhaled or exhaled refers to a point in time but does not encapsulate the infinite diversity of responses to the process of dying and ensuing loss. Death remains an overwhelming emotional, social, philosophical and personal challenge.

The fear of one’s own death is as strong as the fear of losing someone. It is a path that is often travelled together; parents and children, husbands, wives and life partners, even feeling the loss of someone who we do not know but who has influenced our lives can leave us feeling disorientated and alone. It is the routine, a sense of security, a feeling of belonging, reassurance and safety in the predictable measure of the quotidian that we do not want to consign to the past and feeds our distress.

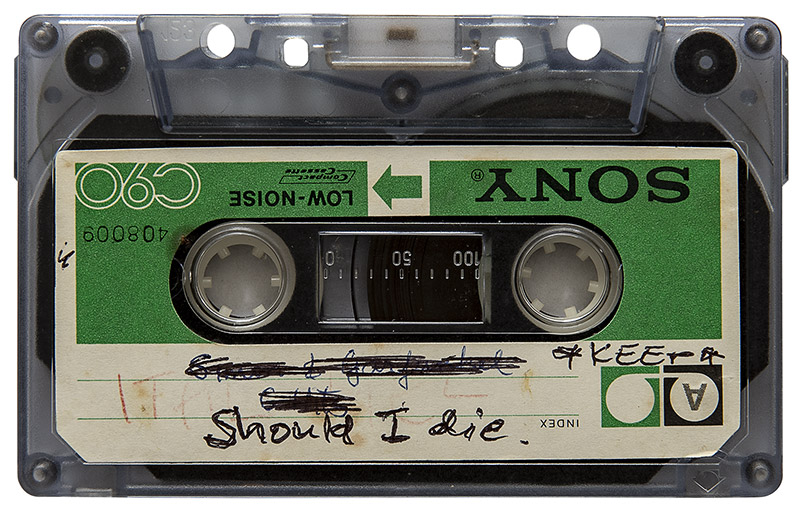

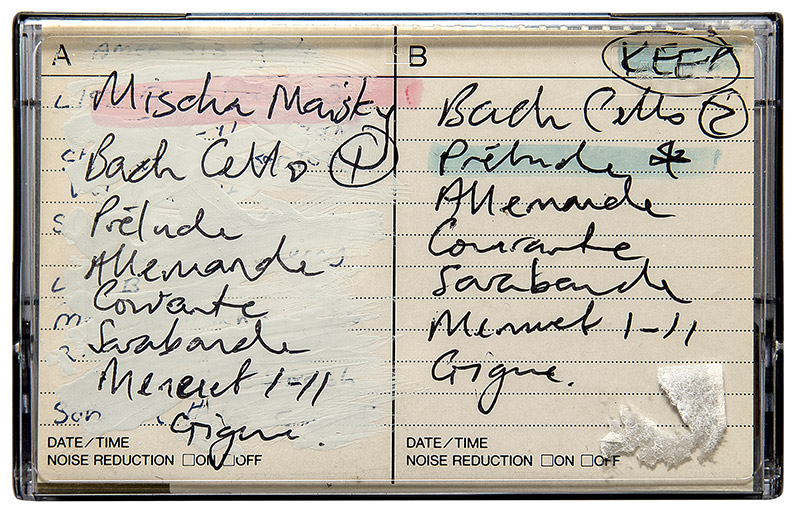

We search for stability, certainty and security while the reality is that there is an inevitable and basic uncertainty embedded in the lives of each one of us. The one thing that binds us all, we are all going to die, without exception. The words ‘Should I die’ handwritten on a Sony cassette tape underscore the grey area between denial and acceptance. The plastic cover explains the meaning of the cassette; a list of musical scores presumably for a funeral. Even using the word ‘Should’ rather than ‘When’, this individual has thought about the end-of-life and has planned elements of his or her remembrance. The cassette tape is also a memento in itself, a redundant and vintage collectable that many are no longer able to play. As one of the many generational symbols that have made their exit from common everyday use, the object itself embodies change and the notion of evolution.

Chris’ photographs document locations related to end-of-life moments such as hospital wards and hospices, waiting rooms and funeral homes. He was also invited to photograph personal spaces in private homes. In many of the photographs the sense of the ‘absence of presence’ is keenly felt in the use of a white rather than a golden light and a softness of tone that although exuding a sense of loss, also generates an affirming sense of calm. White light created by the combination of all the colours of the rainbow focussed on a single point, a symbol of a lived life no matter how long or short. Other images convey a sense of detachment, spatial disruption, a sense of hurriedness where sorrow, suddenness and shock pervade the image. They speak intensely about the instant rather than the memory.

The wet cutlery piled onto dishes in a vintage sink implies the end of something. The crockery and silverware document a time past and while there is no explicit account of what the photograph records, the image evokes a sense of closure. In the top right corner the cold water tap is further suggestion of the finality of life.

Chris’ photographic work seems to build multiple interpretations upon a single narrative. Each image captures a moment, a starting point and does not try to steer a storyline, leaving the context open so that the viewer can be personally triggered by its many potential entry points. In one image shirt hangers, clip hangers, skirt hangers, suits hangers, pink, white, plastic, metal, big, small, all dangle empty behind a door and on a wall. Initially I thought of how hard it is to divest of a loved one’s belongings following a death, a mix of knowing they are no longer needed and wanting to preserve what is becoming memory. The image also simply talks about us, about humanity’s multiplicity and its one communality.

Chris is openly self critical about his own perspective, his intuitive and emotional responsiveness to social and personal complexities.

It is possibly this ability to explore one’s own capacity or shortcomings that have focussed Chris’ interest in deeply personal and private documentary series. Not unlike Six (2013), an intimate look at the meaning of cultural heritage where the most humble of objects can be the most precious testament to who we are; customs and memories that are entwined within them create a social and cultural connectivity, which is active and fluid. Eight takes a further step in that journey.

It takes a singular kind of individual to be able to engage meaningfully with this subject and obtain unrestricted access to people’s most private thoughts and personal stories. The images and the stories in Eight are a testimony of trust in the photographer. It is often difficult to describe one’s relationship to death, particularly through personal experience. Grief and memory is sometimes compressed into silence for fear of diluting its importance and altering recollections. While others speak openly about loved ones, the moment of death, their grief to strengthen the memory, to ensure it is not forgotten and to deal with it openly. The fear of dying is coupled with the fear of suffering, of making loved ones suffer and leaving loved ones behind. Sorrow is as individual as a fingerprint.

Chris’ photo-documentary project Eight was two years in the making. By the time I was able to see the prototype Eight was no longer a project at arms’ length. My own father had suddenly died. I dedicate my thoughts and words to him.

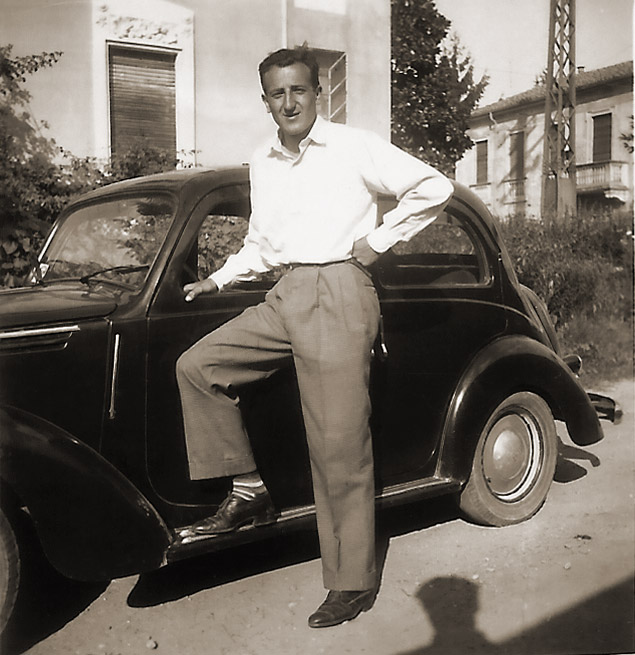

Unknown photographer, Carlo Alessio (the author’s father), ca. 1950s.

Christopher Young, Untitled (2019). Found cassette tape, paper insert, plastic case, ballpoint pen, correction fluid.

Biography

Paola Anselmi is an independent curator and arts writer based in Perth, Western Australia. Over 25 years she has held curatorial and research roles at several prestigious art institutions and collections including the Art Gallery of Western Australia and the Centre for Contemporary Art Luigi Pecci, Prato, Italy.

Since 1995 Paola has focussed on the developments of photo-media in Western Australia and is a regular contributor to Australian arts publications on Western Australian contemporary practice and has published numerous exhibition catalogue essays.

Currently a PhD candidate at the University of Western Australia, her research focus is 20th Century Western Australian photographic history.

The Regional Arts Fund is an Australian Government initiative supporting the arts in regional and remote Australia, administered in Western Australia by Regional Arts WA.

Regional Touring Partner

If the content of this project has raised issues for you or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

All names throughout have been changed and the interviews have been edited for brevity.

Contact Us

Phone: 0421 974 329 (Chris)

Email: write to us!

Newsletter: Subscribe

Web: zebra-factory.com