Eight: The Shift

Christopher Young

Jane, 76

I got a phone call one night [in 1984] from my brother as my father had had another stroke. He said, "Dad's going downhill very fast. He's in a coma. Do you want to come home?"

It's always 'home', you know?

So I said, "Yes! Just hold everything."

He said that they had everything in place for the funeral and what have you... almost.

So I said, "Yes, I'll be home as soon as I can."

I got on a flight the next day and I flew to Ireland. It's a long journey and I got there in the afternoon. They said, "Come on down to see him. He's still in a coma so he won't be able to talk to you."

I went down and I looked at his man in a bed and I thought, "That's not dad! Oh... it is! It is! It is! It's your father." I said, "No! It's granddad."

He looked just like granddad. Of course it was my father. When I looked a bit more closely I saw that it was my father.

It was probably about two years since I'd last seen him.

I went up close and I put my hand on him and I said, "hello dad, it's Jane. I've come all the way from Australia to see you so you better wake up!" ... and he woke up! [laughs] He woke up! And they all went, "Oh my god! Oh my god!"

[The prodigal daughter returns!]

He revived, in so far that he could revive because he really wasn't well. He lived for another four months after that and then he did die.

I stayed with him in his room for three weeks. We went out for walks here and there all the time I was with him. I would talk to him but we couldn't really talk. He could speak but he didn't really know what I was talking about. In some sense he did. I knew he did.

He cried every now and again. I'd mention things and he'd have a little weep. Sometimes he'd say things like, "Are the chickens in? Are the cows in?" because he grew up on a farm. We'd say that Mark is checking that and they'll be alright.

I had to leave after the three weeks because I was working in Perth and I couldn't stay away any longer.

I went in and I sat with him. I said, "Look dad, I'm going to have to go now." Tears started to come down. I thanked him for bringing me up as well as he had, for all the love he put into me and all the care he took of me. He sent me to a nice school and all the sort of things you'd like to say. I couldn't think of anything else really.

I didn't say the things I didn't like [laughs]. I just said the things I did like.

Then I just gave him a hug and off I went. It was the worst thing to leave that house! I was in bits! Just in bits. I didn't think I'd be able to make it home back to Australia.

I'd travelled by myself as my kids were still at school and my husband at the time was working. He was a teacher.

My brother-in-law decided he'd take me up to Dublin. I absolutely didn't want him to come because he never stopped talking and I thought, "I need some space to process this! I can't talk to anybody."

But he insisted and wouldn't take no for an answer. He put my luggage in his car, pushed me in and off I went.

[It's exhausting when you feel like you have to hold someone's hand rather than just look after yourself a bit.]

My father was a lovely man. He was very gentle, very kind, very considerate. He wouldn't say anything quickly or lightly. He would think about it and then he would say something. He was very dutiful and he did everything 'well'. He always had a philosophy that you must always be kind. Don't have big arguments or anything. Just reason things out.

"Don't leave the table full. You've got to leave the table before. Just take a little bit of food and when you are satisfied with that, that's the time to finish."

I've always remembered that but I haven't always kept to it! [laughs] I've taught my kids it. One of them took it on but the other one didn't but that's alright.

He grew up on a farm. He was the second eldest son of seven children. The eldest one would get the farm and worked on the farm.

My father didn't really want to be a farmer as it didn't suit him. He went into the town and he worked in a drapery shop. He liked the business of mingling with people because he was quite sociable.

Then he decided he would like to be a sales rep for the manufacturing company who supplied the shop. He applied for and got that job. He got a lovely station wagon and he could carry all his samples around from town to town and visit all the other drapery shops in that town. He would open up his wares then they would place their orders.

It meant that he was missing from the house from Monday to Friday. He was on the road for a week and he would come back late on Friday afternoon.

He had hired a maid to look after me and he had hired a washer woman to come and do the washing on a Monday.

I was an only child from that marriage. I used to miss him an awful lot. I used to hate him leaving and I would hang onto him as long as I could... like a limpet! [laughs]

My hands were around his neck and he would go, "You've got to go get ready now. You've got to go and have your breakfast", then he'd be gone.

He always came back with a bag of Granny Smith apples wrapped in purple tissue paper from Spain or somewhere. It was lovely. It was perfect.

He remarried when I was seven. I didn't take to my new mother at all. We got on. We had to get on but we were never on the same page. The saddest thing for me was that fact that when he married, it was as if he handed me over to her. He didn't involve himself with me anymore. That was really painful. I couldn't understand it.

I just knew I was not happy and I used to follow him around and he would sometimes talk to me or sometimes tell me to go off.

It wasn't the same. It was totally changed. I don't know how the marriage was but he wouldn't come back every weekend, he would come back maybe six-weekly so he was missing even more. I got to the point where I couldn't really speak to him anymore. That was really hard.

My new siblings and I got on alright, we had to get on. She used to make me do a lot of housework and cleaning.

I had a step brother come about two years after the marriage. Three years after that she had twins, a boy and a girl. They were gorgeous! I love my brothers and sister, they're just lovely. They're more like my dad really [laughs]. They're funny and they're warm and they're kind.

I'm the oldest. I was about 10 when Tom was born and 13 when the twins were born. I was the other mother. She adored Tom and the other two were my 'charges'.

I didn't have a lot of fun I have to say. There'd be school and I'd come home as slowly as I could then straight away into looking after the kids. It was tough.

I think it was hard times. My stepmother didn't like living in the town where we first lived. She wanted to move back to the town that she came from, which was Cork, right at the bottom of Ireland. So we had to move there. We had to buy a house there and it was tough.

My father had to move to Munster, the southern province, to find work with the same company there. He wasn't known to the clientele so it took him a while to build up that relationship again which wasn't good for him.

He [eventually] left that area and went back to his own area. It meant that he was away for six weeks at a time.

My stepmother came on to the scene in the beginning of the 1950s. I lived in Ireland until I was 18. As soon as I was 18 I left to do nursing in London at King's College Hospital. I didn't finish that. I probably worked for 18 months because I had a boyfriend. He wanted for me to give it up so we could be together more and get married and all that.

It seemed like a good idea. I didn't really want to leave nursing as I quite enjoyed it. In retrospect it was probably a good idea.

I went into an office and I enjoyed that. It was very 'cool' with all the mods and the rockers at that time. It was quite a shock going from Ireland to that! It was great.

I got married there and my daughter was born there then we moved to South Africa.

We were planning - I had forms and everything - to go to Western Australia. My husband came back one day and said, "There's this great offer in South Africa for teachers on contract." You could go for so many years and they would provide you with a beautiful ranch-style home.

We were living in a two room apartment at that point with a little baby so it sounded pretty good. He signed up for that and said, "After that, we have got to go to Australia. I don't want to stay there for very long."

We lived there for eight years. It was supposed to be a stepping stone but he got a promotion. He was doing well in South Africa and he was at Uni, lecturing there. He loved it but we had to leave South Africa because it was the beginning of the troublesome time in the 1970s.

He wanted to go back to Ireland because he was homesick and wanted to be with his family.

I said, "We'll go back to Ireland just for a little while", but we won't live in Galway where he was from. I didn't like Galway. It's a beautiful place but I didn't ever feel at home there. I liked the Midlands and flatness and the place where I came from.

We went back for six years. It was good for my kids because they loved it and they got to meet all their cousins and relate to them. I think they loved it in one way but they were quite happy to come somewhere else.

I left it with them. I didn't sell it. I said this is what it's like and there will be problems when you go there. You'll have to get a new school. You'll have to make new friends. You're going to feel a bit strange.

We move to Australia in 1978. My daughter was 14 and my son was 12 1/2.

My daughter settled in alright but my son settled in instantly! He had a really strong 'Ocker' accent within 10 minutes of landing [laughs]. He was determined to fit in. We couldn't understand him! [laughs]

My father was upset about it. He didn't like it.

The reason that I was really, really motivated to leave Ireland was an incident that happened when my stepmother's sister died. She had lived in our home for many years and then she went to America to make her fortune as a private nurse in New York.

She was there for quite a long time. She used to send us wonderful parcels of recycled clothing and we'd all forage around in there and get things to wear. They were just beautiful.

She got stomach cancer and she died late 1977. She was lovely. I just loved her. She was great. She was a compulsive knitter. With really fine wool she used to do these beautiful little jumpers for the kids with little characters on them like a comic strip. It was amazing!

She got this cancer and she came back from New York. She was in hospital almost straight away. She was really bad. I used to go and visit her. I knit her a beautiful cardigan and she loved it.

Then she was really in extremis and she was going to die. My stepmother was just worn out. I went into the hospital one day to see them. Her sister was lying there and you could see that it was only going to be a day or two or three at the most. I looked at my stepmother and she looked so haggard and so sad and so worn out, sitting there night after night.

I said, "Do you want a break? I can sit for a while and I'll ring you the second if anything changes."

I don't know what was going through her mind but she leapt up and she took me by the shoulders and she pushed me backwards towards the door. She said, "This is only for family!"

That just did something to me that I'll never forget. It was such a powerful rejection. I did confront her with it later on but she said, "I'd never have said that! I'd never do that!"

I can understand, she was emotionally overwrought but it sat there and I can never get rid of it. I never mentioned it to my father. He was sitting outside as he wasn't obviously part of the family. I couldn't speak to him. I can't tell him this. I can't tell him what happened. He'll be devastated.

He must have known that something happened because I came out and I just looked at him. He just sat there and he looked at me and I just turned around and went off. It was horrible.

It was destructive because the power of it was so strong and the vehemence with which it was delivered was so strong. The fact that she held me and pushed me out. She almost didn't have to say anything.

I wanted to leave [Ireland] straight away. I wanted to leave anyway. I was sort of iffy at that stage but I thought I'm not staying in this town any longer. There's no place for me here.

So, we went to Australia and my father said, "Could you not get further away?" I said, "No, I couldn't. You don't understand."

I had two children so he got to love our two children. We brought them back once, probably a few years before he died.

He had a stroke and that just finished him, very quickly. There was no reprieve this time. He was gone.

They phoned me, of course, to tell me that he had died and did I want to come over and I said, "No. I've said goodbye. There's no point. I'd like to be there for the other three [siblings] but I can't come."

Six months before I'd paid for a trip. I couldn't do it. We weren't that wealthy. There were no cheap airfares [at that time].

I said that I will be thinking of him.

After he died I couldn't talk to anyone about it. My husband didn't want to talk about it. I came out and said, "Dad's died". I just wanted to talk and I wanted him to hold me or something. He just said, "I'm dreading a call like that." He just went on and on about how he would feel if that happened to him. I thought, "Right... I'm shut out. I know where I am."

He's fantasising about this thing that hasn't happened. His parents are perfectly well.

I just walked off. I didn't want to be with anybody.

Because I didn't go to the funeral, I felt I needed to do something. I did organise a little service at the chapel in the city in Perth. There's a little chapel there that used to be called All Saints Chapel. I found it by accident one day when I was feeling really low soon after I had come to Australia. I didn't know anybody so I just wandered in and sat down. It was lovely. Everything was orange and it was like a warm flame. It was just beautiful with lovely settees. These long banquettes of velvet covered orange.

It's still there. They've recovered the lounges. I popped in a couple of years ago and I thought, "Oh no... it's dead. Whatever was there isn't there anymore." They have a different group of clergy there now from the Diocese which is hard as nails. It didn't do anything for me and I thought no way will I ever come back here. I liked it the way it was. [laughs].

My stepmother is still alive. She's 96! She's got dementia and some faculties but she falls regularly. She never breaks anything. Gets hospitalised occasionally, bounces back... she's just amazing.

I think she was quite happy that I didn't come back for the funeral. [laughs]

We don't really have contact any more because she doesn't know me. She doesn't know who I am. The last time I phoned was a few years ago. When we were talking she goes, "Thank you dear for your call and all the best now."

The processing of my father's death happened later, after my marriage finished. About 10 years later. That was when I mourned my father. For some reason I couldn't do it until then. Because nobody was there to support me.

When I was on my own, I bought this lovely little place in Scarborough (Perth) and it had a lovely big courtyard in the back, all grassed.

I was sitting there one day and I thought, "I need to do something for my dad. I really need to do something."

He was a very strict Catholic and I was always supposed to be a very strict Catholic so I thought I'd go to a mass, just an anonymous mass where I'd just pop in. I found out what time the morning mass was on. I didn't want to go on Sunday or anything like that so I just went to a daily one which are usually pretty snappy.

I wore black from head to toe. I sat there with the funeral mass and I was reading all through that myself while he was saying whatever he was saying. I named my dad out loud in the course of that which was nothing to do with anybody else.

Then I came home and I said, "What would they do in Ireland? They would have ham sandwiches and sherry." So I bought some ham and one of those awful white loaves of bread and a bottle of sherry. I went home and I opened the sherry and I made the ham sandwiches. I sat down and I had a few of those and thought, "God! At least I'm doing it."

Then I wrote a eulogy and sang some hymns. Anything that I could remember. I couldn't remember all the words.

[You did this all by yourself?]

I did. I actually went to a counsellor and she said, "You've got a lot of grief in you." She picked that.

She said, "Just do everything you can think of to do with it and get it out."

He used to write me a lot of letters and I never kept any of them. I was really disappointed that I didn't have any left, even one.

I stood up, lit a candle and spoke the eulogy out to the garden. I then burned [the piece of paper with the eulogy on it] and I thought I'd bury the ashes. I bought a little Casuarina Tree from Kings Park. I dug a little hole and put the ashes in it. I did all the Greek throwing the ashes on yourself and keening and yelling and all that. I hope nobody was listening because we were all quite close together. It was lunchtime and most people would be at work. It was irrelevant if anyone heard and I didn't care.

I was still in my black and I rubbed earth on my arms and my chest and I wailed and I did all that stuff. It wasn't really natural to my culture but I have seen that happen with Greek people so I'll do that. [laughs]

I did whatever I could.

Then, after that, I came home and said, "Let's have a céilí." I got Irish music and I played all that. A knees-up! On my own again, loud as I could and danced all round the place. A bit more crying here and there.

I felt as light as a feather when I'd finished all that. Absolutely like I was a feather. It was all gone. All that grief was gone.

It was one day and I did the whole day until about 8pm when I collapsed and went to bed.

[Hopefully you didn't drink too much sherry along the way!]

I didn't like it really. I had a few. I had a whiskey! I got whiskey as well because my dad loved whiskey. He loved Black Bushmills whiskey so I got a bottle of Bushmills whiskey as well.

[There's two stories I really like. This idea when a lot of the Irish were leaving the old country to come to Australia or to New Zealand they used to have Wakes before they left.]

An 'American Wake' they used to call it. Not that they were all going to America but I suppose an 'Australian Wake' if you were going to Australia.

[This whole idea of having their funeral before they left.]

Because they were never coming back. It was a one-way trip.

[I also love this idea - like you did - of creating your own rituals.]

My father was buried. There weren't any cremations in Ireland because we're Catholics you see? Mostly they don't do that. Well... they do now. They do what they like.

I was taken back to visit his grave. I wasn't going to go myself because graves don't interest me. I don't mind going to a country town and looking over a graveyard. You can kind of piece together a family history from all the people who are named and the people who are next door and the people who are behind. "Oh gosh, they died very young" and all that.

I don't have any connection to the grave. There's nobody there. To me it's just a pointless exercise. I mean it's a beautiful monument with marble and everything like that.

He's buried with my Aunty actually [laughs]. My stepmother's sister. She died first so they got a plot for three.

[The irony of that!]

It is funny, isn't it. I thought it was hilarious! It's got their names in gold, embossed in the marble. There's room for stepmother too, assuming she goes before the kids. You don't know.

Visiting a counsellor did help me a lot. After I left my marriage I was in bits. I felt I was haemorrhaging, physically haemorrhaging and I couldn't stop it. I felt I was dying ... that's exactly how I felt. I don't know what it was.

I didn't want to leave my marriage. My husband was an alcoholic and I just couldn't take anymore. It came to a point where one last thing happened and that was it. I was gone. Two days later I was gone.

I said, "I've left my marriage and I just can't cope." It was probably a year later that I did that. She said, "Have you had a lot of grief in your life?" I said, "Yes, well I have."

She wanted me to do a grief graph. I'd never heard of a grief graph so she showed me. You start off when you were born and [include] anything that happened that you would possibly grieve over to where you are today. You should include pets, friends, lifestyle, home ... all those things.

I started doing it and I thought, "Oh my god! No wonder I feel so bad!" You just move on don't you then you have this cumulative effect. I didn't know you'd have a cumulative effect with all those things that happened.

I said, "What about my mother? That's a significant loss. What can I do about that?" I didn't even remember her. I was 10-months old.

She said, "That's pre-verbal so you will never have the words to explain those things and how you felt. You will certainly have it in your body. That is profoundly in your body."

[If you were 10-months old you would have known. A lot of the touching you would have experienced as a young child would have essentially gone.]

Anytime I really feel devastated I go from room to room. I want to go to the corner and I want to sit down there and howl. I think that comes from then. I wasn't walking and I always have to sit down.

[At one stage] I was working in a counselling agency and I said to a counsellor, "I always feel really devastated around January. I don't know why. Every year it comes on me and I just want to weep all the time. Any little thing will set me off."

She said, "Did anything happen in January? Maybe when you were a child?"

My mother died in January and she thought that's what it is. Your body remembers.

[It could also be association. Especially as a child you tend to mirror what is happening around you. For example, if your father was very sad around that time of year you would have picked up on those emotions.]

It certainly was a factor. Even today. Not every year but every now and again in January. It all takes me unawares and I'm not prepared for it because you are carrying on and busy and people are coming and going. Then I just want to cry.

I did counselling for five weeks. I couldn't afford counselling so this was a trainee counsellor who had qualified but she was just getting her numbers up or whatever she does. It was five weeks and I think it was $5 a session through the Women's Healthcare Network or something. It was an hour each time. I knew I had to do all my work in five weeks.

It was fantastic. It really was good. She was very, very helpful. Very unusual and I have never come across anyone like her. I can't remember her name but she was really good. [laughs]

I never talked to my siblings about his death. I did write to my stepmother at one stage when I was going through this counselling business. I wrote and confronted her with what she had said to me. I said, "This is what you said to me and I want you to apologise. It was unforgivable and I have never forgotten it."

I heard nothing, absolutely nothing back for probably six months. My brothers and sister wouldn't write to me. Nobody would write to me. I thought, "Oh well.... If that's the way it is then that's the way it is."

She was very upset apparently and created havoc at home and sobbing and "how could I treat her like that? How could I say these things?"

That wasn't good for my relationships with them. I think she was very happy that I was far away.

She wrote back eventually. Obviously my brother had a hand in that. It was very legalistic. She said, "I can see you are very troubled and I don't know why that is. I do understand that you have left your husband. That's understandable that you would be emotionally overwrought."

It was all because of that, that I 'imagined' that she said these things which I have never retracted on. I said, "Those things were said to me by my stepmother."

They were there in that room but they didn't probably hear it because she was right up to me like this. She had her back to them and she was facing me and I was being pushed out the door.

They did say to me one time that mum was really upset by what I said. I said, "Well... she said it."

I thought, "I don't belong here" so I'll take myself off.

I didn't try and persuade them but I did say to my husband that, "We were always going to go to Australia so we've got to go. We'll have to talk to the kids and see if they really want to come. If they really don't want to come then I won't do it but I do want to move from this town."

I was very aware of mortality because of living in rural Ireland. I spent a lot of time on my grandparent's farm which was very remote. Death was very familiar. You just went and saw dead people. If somebody died in our neighbourhood we, as kids, used to wander around looking for a black ribbon and a white card on the front door with the name of the person, RIP.

It meant that the body was inside and they would welcome anyone to come in and say a prayer and share their condolences.

We, as little kids, would knock on the door and we would go in and we would be welcomed. You'd be brought upstairs to where the body lay in their bed, all dressed with their Rosary beads in their hands and joined like that. Looking very dead actually. Maybe half a dozen people, neighbours or relatives sitting around, looking and being there having a vigil. Some times they would say prayers and you would kneel down and say prayers with them.

Then, after a suitable amount of time, maybe 10 Hail Marys or something you'd get up and you'd say, "Excuse us now, we're going to go." You'd always say sorry, "I'm so sorry." You didn't know. They were all pretty miserable actually.

They'd smile at us and off we'd go down. Then downstairs there'd be lots of cake.

[I was just wondering what the motivation was as a child!]

[Laughs] There was an ulterior motive ... Definitely!

When we were praying, we would always look at the body very closely. You know, was it moving? Was it breathing? You'd check the chest. Was it moving up and down? You could see that they were absolutely dead. They were like alabaster. So white and thin, transparent skin. Mostly old.

[Do you think that's a familiar story for many Irish kids?]

From my era yes. Not now. It's just like everywhere else now. You're whisked away and nothing's seen or heard of again.

We did that a lot. We'd have our cake and say, "Thank you very much" and smile and off we'd go, skipping around the path. "What do we do now?" [laughs]

People would come to your house and they would prepare the body. Everything was done by the family and the community. The Undertaker came in with his hearse and brought a coffin. Put the body in the coffin and off they went.

You could have the body at home for a couple of days. They didn't embalm, it was completely organic. Everything was as it should be really.

You just get washed. Your hair gets combed. You get dressed in a shroud. Usually a brown shroud. They're always brown shrouds. Dark brown.

Some times people would be in a blue shroud. I asked, "Why do some people wear blue?" I was told if they belong to a group in the Church called 'The Children of Mary' they could wear blue when they die. She's always in blue. I thought, "I want to be buried in blue! I don't want to be buried in that horrible brown colour." So depressing! [laughs] So, as soon as I was old enough I joined 'The Children of Mary'. [laughs]

[So your motivation was that you liked the colour blue!]

[Laughs] It's all gone by the wayside now. I don't know what they do but they do what everybody else does.

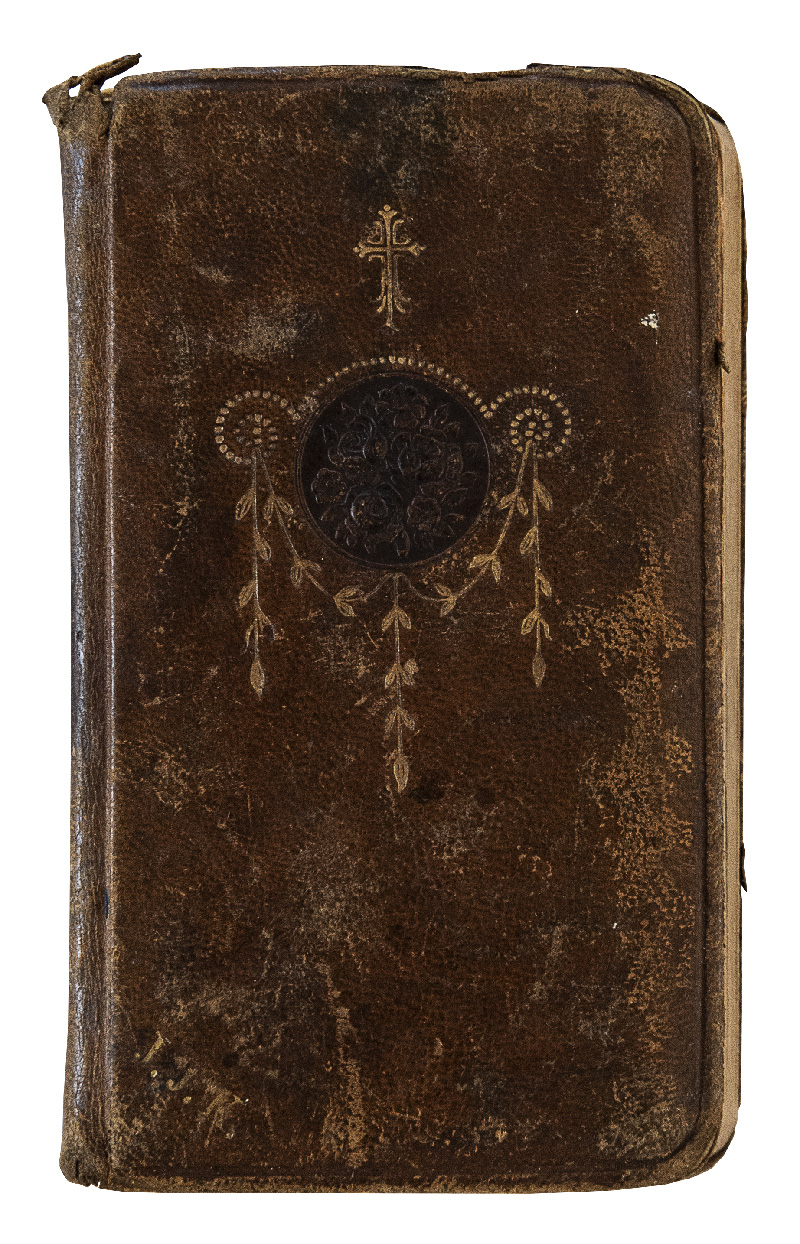

I've got [my father's] prayer book that my mother gave to him when they were getting married. She was very religious too. Everybody was. There's wasn't a lot to do and it was social.

I did have a Rosary Beads but I think I gave it to my daughter that I had given to my father. My aunty from New Zealand came to visit and took me to Lourdes in the Pyrenees on a pilgrimage. I bought Rosaries for everybody because that's what you do and I gave him this lovely, deep purple one. He had it all his life and then he gave it to me and he gave me the prayer book.

I kept the prayer book because it was both of theirs in a way. Very well worn but [with a] beautiful leather cover, all embossed. I don't use it. It was in the days when the Catholic Church prayers were in Latin. It's got the English translation but I've never read it. I've just looked on the inside cover and it just says, "In remembrance of 11th of August, 1941" and then 'S'.

They weren't exactly demonstrative or overflowing with romantic words. 'S' was my mother. She was an orphan as her parents died when she was 11-years old. She was the youngest of seven children but a lot of them died in infancy. She died when she was 29. She was brought up by my grand uncle and his wife in the town that we lived in. That's where my father met her.

She died of Tuberculosis. That was rife all over Europe. It was just about the cusp of the time when they had the cure for it but it was too late for her.

I don't think the death [from Tuberculosis] is quick. It takes quite a few months. She had a miscarriage before me and that weakens you. She would have probably got pregnant again straight away and then I was born. When I was 10-months old she died. She was very sick. I've got a photo of her in town, wheeling a pram in which I'm probably lying and looking really sick.

My father would not talk to me about her at all. We had a little pile of photographs which were on a dish - of all places - in the china cabinet with a lid on it. I would say, "Can I look at the photographs?"

I'd take the lid off and I'd take all these photographs out. They were all of my mother and him and on their honeymoon, me when I was a little, tiny baby. She's holding me and he's by the pram and he's taking the photographs. Very early photos of me and that was it.

I would ask him to tell me about her. He'd say, "I'll tell you one day. I'll tell you one day." But then later on, I did ask him. I was sitting with him one day when I was in Ireland and he said, "You know you've got your mother's hands?"

I said, "Really? I didn't know that." [laughs] He said, "Yes you do. You're like your mother." I said, "Will you tell me something about her?" He says, "I can't. I just can't. I just can't."

[He obviously took it pretty hard.]

It must have nearly killed him. Awful. His sisters came and nursed her at home until she died. One of them stayed on for about nine months and helped look after me.

He wouldn't talk about her so I don't know much. I did try to find out things about her from her best friend. I thought I'd try and write to her. I knew [roughly] where she lived and I got google maps and I looked up that street. I found the name of that street and I wrote to her in that street with no number and hoped that it turned up. She was actually in that house.

She wrote back to me and said, "I remember your mother but I wasn't her best friend. Her best friend was my sister." She said she'd write to her sister because they used to correspond. I said that I'd love to see something of hers or know something about her. "Can you tell me anything about her?"

She was more interested in talking about herself all the time. I thought that was a waste of time. I just left it thinking what can I do.

Probably about a year later I got this package from England, from the sister of this person, with letters that my mother had written to her. She sounded so delightful! I just loved her straight away. It was really lovely.

[It's nice to hear the 'voice' of someone. You can connect to it more.]

Notes

King's College Hospital is an acute care facility in Denmark Hill, Camberwell in the London Borough of Southwark, referred to locally and by staff simply as "King's" or abbreviated internally to "KCH". Source: Wikipedia.

Céilí dances, or true ceili dances are a popular form of folk dancing in Ireland. Ceili dances are based on heys, round dances, long dances, and quadrilles, generally revived during the Gaelic revival in the first quarter of the twentieth century and codified by the Irish Dancing Commission. Source: Wikipedia.

An American Wake was a ceremony for emigrants from rural Ireland to the United States. The custom prevailed among Catholics, especially in western Ireland where traditional customs remained potent. Many Catholic country people still regarded emigration as death's equivalent—a permanent breaking of earthly ties. Usually hosted by the emigrant's parents, the American Wake was attended by kinfolk and neighbors, featured the liberal consumption of food and drink, and exhibited a seemingly incongruous mixture of grief and gaity, expressed in lamentations, prayers, games, singing, and dancing. Source: encyclopedia.com

The Regional Arts Fund is an Australian Government initiative supporting the arts in regional and remote Australia, administered in Western Australia by Regional Arts WA.

Regional Touring Partner

If the content of this project has raised issues for you or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

All names throughout have been changed and the interviews have been edited for brevity.

Contact Us

Phone: 0421 974 329 (Chris)

Email: write to us!

Newsletter: Subscribe

Web: zebra-factory.com