You can’t get there from here

David Bromfield

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

And time future contained in time past.

If all time is eternally present

All time is unredeemable.

Burnt Norton I, The Four Quartets, T. S Eliot

You should start somewhere else.

You can’t get there from here.

Advice to tourist inquiring for Dublin from porter at Limerick station

Christopher Young begins small town with a beautifully ‘timeless’ image of an ancient gate and a loading ramp for sheep and cattle. Mist dissolves the outlines of the grasses, hedge and trees that cover them. There is no way in or out of the field beyond. The ramp ‘crosscuts’ vision (/) a barred invitation. All that can be seen beyond, unless one were to work and walk through damage and decay, is the fading blue mist of night to the left and the pink tinged sky on the right. This is not long after dawn at the beginning of his most courageous project.

His second image made at 8:00 am is an empty, equally romantic country road, where, later that day he smiled at a woman taking her child to school. Next day, he says, a honeymooning couple was killed on the same stretch of road. Clearly the photo and the events along it are only connected by memory, but this may no longer have any magic or consequence.

It is brave to return, with your memories, to a place that you last saw 27 years ago, especially if you are a photographer looking, not so much to re-animate those memories in your new project, as to re-engage with the icons of place and community that have prefigured what you are now as person and artist. In fact, Young found it impossible to ‘gain access to [his] childhood’. He chose other riskier ways to engage. He set about making images in which the human was inscribed, locked beyond the reach of memory and failings.

Not long ago photography was, by its very nature, capable of an active partnership with memory. Every artist-photographer knew (or hoped), that as soon as the shutter was pressed, the image would exist through time for themselves and others. In a sense every photo would become an icon. An evening with the photograph album was once worthwhile, not just a dull reminder of the immediate poverty of the moment.

Walker Evans, the American photographer, was a confident, competent maker of icons. He used his camera and the resources of the photographic culture, the apparatus made available by modernity, to shape landmarks from the shifting sand of memories. That is why his work is still potent, still part of this world. In his 1964 lecture at Yale, he defined this process as ‘lyric documentary’. He closed the lecture with a discussion of some popular American postcards, which he collected, mainly views ‘Downtown’, in which he evoked the role of memory in opposition to sentiment.

The medium was hack photography; but those honest, direct little pictures have a quality today that is more than that of mere social history… The picture postcard is folk document. To taste them properly one should renounce sentimentality and nostalgia—that blurred vision which actually destroys the authenticity of the past. ‘The Good Old Times’ in any event, is a cliché of the doddering mind. That said, one can, in any effect, re-enter these printed images, and situate oneself upon the pavements in downtown Cleveland, Omaha or Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts…

In the street the trolleys clang, the air is not at all free of horse smells…

One’s own father’s office was on the fifth floor front. And yesterday he paid the bill for your first long pants. Somehow this can remind you, now, that there was nothing amusing about first love, juvenile ineptitudes and early glory.

Other postcards also offer evidence for the once iconic nature of the photograph. Some time ago the London artist Susan Hiller demonstrated that an identical waveform appeared in photographic souvenir postcards depicting the promenades of many widespread British seaside towns; an irrefutable original icon of time and place was in fact represented by a universal hieroglyph.

Evans succeeded, almost intuitively, through the lyrical engagement of art, with photographs that ‘travelled through time’. Young found it impossible to re-enter his time-bound childhood in situ and instead opted for a simple short-term presence, a celebration of his small town for his new work. This was no personal problem. The apparatus of photography, both camera and context has changed beyond belief in those 27 years. I doubt that I have thirty photographs of my childhood, but they are all icons. I vividly remember the photographer coming to pose me, and my baby brother on the back of our sofa. His black and white prints are lovingly hand-coloured and framed. For our youngest daughter, we had the benefit of photo labs, then the many incarnations of digital technology and the Internet. We have tens of thousands of images. Most have never been printed. It has often been argued that all photography, by its nature, redefines the poetry of experience.

These recent changes have eroded memory and robbed photography of its innate ability to travel through time intact. The rostrum work in Ken Burns’ movies, notably Jazz (2001) and The Civil War (1990), is much more an acknowledgement of the fading power of photographs as icons than a triumphant recovery of their vitality. The most compelling use of photography in film remains Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962), a 28-minute film composed almost entirely of still black and white photos, in the high contrast manner of Life magazine. Marker used their remaining iconic strength to tell the story of a time traveler from a future after WWIII, whose uncannily accurate memories of his childhood allow him to make the journey. This intensely lyrical film contains a remarkable commentary on the existential relation of photography to time and its poetic rebuilding of other times and places.

By 2012 photography had changed. Time travel was out for Young and everyone else. However, if you are a committed artist photographer, with a good eye, the goal must remain the same, prescient, stable, even beautiful photography, brought into existence with the best possible relation between technique and poetry. To this end, Young chose a gentle presence, an immersion in the community that ruled out the role of a documentary recorder.

I was interested in James Agee’s bug-ridden immersion…. The blurring of ‘art’/documentary is really interesting to me. How ‘non-artified’ images can twist people around, often uncomfortably.

It was a difficult balance between the perception of nostalgia and romanticism I might place on my original experience. I was conscious that it would be a remarkably different experience but was equally shocked with how intensely familiar and comfortable it all felt.

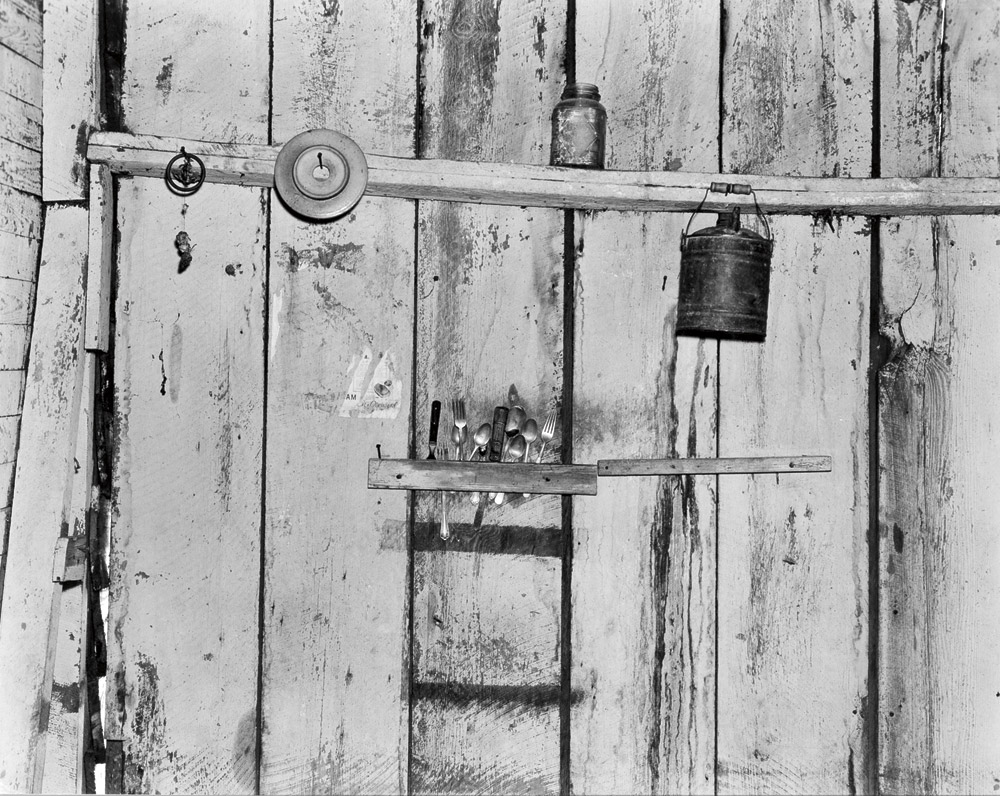

He chose several ‘subjects’ that offered him a reasonable opportunity to get close to the current social state of small town. The first was a day spent duck hunting, with ‘Jason’ a farmer who posed, awkwardly, outside his island hide, standing between the hide and a sheet of water covered with decoys, for a single shot, oddly reminiscent of Walker Evans, before disappearing into it. The next image of a hide, alone with its mossy duckboard lying across rippled water is a far more successful, even beautiful photograph. The two together speak powerfully of circumstance. The final image, a still-life of table and shelves in the main hut with various objects associated with cooking spread all across the picture plane is the most technically accomplished and the most successful as a single image.

This mode of still life composition can be traced back through Evans to early American trompe l’oeil painting and forward to recent photography. The best, the most human and most powerful examples of this consist of still lives, empty interiors and infinite traces of the human, but no one is ever in sight. The finest piece in the recent Jeff Wall exhibition in Perth was a small, early still life of a stained sink. Stephen Shore’s still lives and banal objects are nearly always his best work. These images seem to say ‘it was like this when the music stopped, nothing changed.’ The absence of presence still leaves room for poetry. It has other sources in modern photography, surrealist images of flea market objects for instance. Developing his earlier writing on American painting, the critic Michael Fried has argued for a kind of formality, a dedicated absorption, an absence of ‘theatricality’, in recent photography. Images of absence in presence do offer the best chance to recover a version of the photograph as an icon, but one that no longer relies on memory.

Throughout the remainder of small town, Young presents a cascade of such images. He focuses on two social activities, lawn bowls and the town ‘brass’ band. An image of a man in his socks, standing in the open doorway of a small weatherboard house follows the compositional strategy of the ‘American’ still life. He, his shadow, his improvised vice and various well-used objects are placed on the picture plane, carefully located against the informal grid of weatherboard walls, windows and all important shaping shadows. The jagged vertical at the edge of the sunlit wall to his right seems to be just on the golden section.

Presumably he is a bowls player, as his is the only human image in this section. A view of a vase of flowers through a window follows, also framed by weatherboard and shadows. Empty coat-hooks on the weatherboard stress the absence. The two images have structure and vision in common.

This amplifies the human trace in the second image. A double-page panorama shows bowling bags, a single bowl and kneeling mats, wedged in like fossils in rock strata, above and below the central line of a white painted wooden shelf. Young has cropped the image top and bottom so as to catch the worn familiarity of their shapes and textures in incomplete shapes. Only the bowl has a full outline. Details of stitching and handles intensify his social archaeology. The image repeats further on, in a poetic consummation. A different format reveals the full shape of the bags round the bowl.

The most formal, most abstract relic of the bowls club is Young’s best account of human traces, the human presence in absence. It shows a stack of long wooden scoring boards painted in different colours. Numbers, names and a patch of circular red tags on hooks combine in complex rhythms. Everything is worn by use so that each shape forms part of an informal poetic pattern, set off by the curves of the silver trophy in the lower left corner, the perfect lyrical document.

There is more human presence in Young’s pictures of the brass band and its environment. He was able to share memories with some band members who had survived from his childhood. He presents their images like saints with the emblems of their martyrdom. He also achieved a portrait of ‘Robert’, the Tuba player that has something of the intensity of the figure studies of the German photographer, August Sander. Robert occupies the frame, right up against the foreground. He holds his tuba flush with the picture plane, so that it fills the pictorial space from corner to corner. This is the closest Young comes to an iconic memory, but even here the impact of the image depends on a tight formal structure.

His final group of images comes together as a concise short essay on the human trace, on presence in absence. It raises directly the question of his primary childhood memory, of playing in a big abandoned building with abandoned objects he and his friend had collected. These remnants of the work should remind us that the workplace is always a place of inscription. Old objects and buildings reveal the humanity that is inscribed in them through their making by human labour.

An image of an old factory power board with large round dials framed behind a dilapidated furnace suggests human making, purposeful patterning, formable lyrical fabrication rather than the purely iconic, may be the way forward for photography. The writer J.G. Ballard described his experience of similar human inscription.

I am always struck by the enormous sort of magic and poetry one feels when looking at a junkyard filled with old washing machines, or wrecked cars, or old ships rotting in some disused harbor. An enormous mystery and magic surrounds these objects. I remember not so long ago being in the Imperial War Museum where they have the front section of the Zero fighter cut through the cockpit… looking up into the interior, one can see every rivet. An enormous sort of tragic poetry surrounds that plane in the Imperial War Museum. One can see all those Japanese men at work; women in their factories in some Tokyo suburb stamping the rivets into this particular plane. One can imagine the plane later on a carrier in the Pacific.

Young’s small town also contains a tragic poetry. From social institutions to abandoned factories it too is a single human artifact, made for purpose, surrounded by mystery and magic. Young’s almost shamanistic childhood games with objects abandoned in a long deserted factory shed was an early attempt to animate or rather reinvent the world around him. It formed the perfect figure for his photographic strategy of recognizing the inscription of the human everywhere in small town, the town site where memory and the lyrical emerge full of life. He has succeeded in making some superb photos in which all of small town is powerfully inscribed.

This text was written by David Bromfield to support the Small Town project.

David Bromfield is a critic, writer and curator. He has written several books on Western Australian artists including Codes on Jánis Nedéla (2008) and Waves (2009). He and Pippa Tandy were curators of the Bunbury Anniversary Survey (2010). His major monograph on performance artist and painter Martin Heine was published in June 2011.

Christopher Young, Seven #21, 2012/16

Christopher Young, Seven #20, 2012/16

Walker Evans, Kitchen Wall, 1936

Christopher Young, Seven #23, 2012/16

Christopher Young, Seven #29, 2012/16

Contact Us

Phone: 0421 974 329 (Chris)

Email: write to us!

Newsletter: Subscribe

Web: zebra-factory.com